“Security isn’t just a feature, it’s a base, a fundamental right.”– Tim Cook, CEO, Apple

Apple devices are a rage today and it is one of the most successful brands globally. This success story is very closely connected to the brand’s pioneering efforts in securing their devices through advancements in design. This is just one example of the proliferation of the concepts of ‘Security by Design’ around us in almost every sphere of our lives, from the websites we use, to the cars we drive and the buildings we inhabit.

Even though the term is mostly used for physical security, and design is mostly referring to architecture, the underlying idea is the same. To make security more convenient and less obtrusive for the end users while ensuring higher efficiencies. Security needs to blend into the background without discounting its significance. That comfort and belief of ‘being secure’, is a prerequisite for ‘feeling secure’. The absolute faith in the security provided, without consciously having to think about it and the actual physical mitigation of all threats, risks and vulnerabilities is the ultimate quest.

Traditionally the approach in India has been, ‘in-your-face’ kind of security, expected to be more palliative to those being secured and more deterrent to those being secured against. Globally however, the tilt is towards the covert approach, with greater emphasis on human dignity and sensitivity to the psychological implications of militarization, that most in India have no better option than to endure on a daily basis. These are reasons enough to explore the resurgence of ‘security by design’, to evolve the security climate in our urban context.

Resurgence, because the theories go back to the beginning of civilization. All human efforts to ‘feel secure’ and all architecture, originated with the need for shelter against the elements, animals and later fellow humans. What started as a simple fence of twigs and branches around a settlement has today acquired more structural and social dimensions but the underlying purpose continues to be to serve as the first line of defence against the unseen enemy.

Physical security today is dominated by mechanical devices like cameras and scanners in addition to personnel and guards. But it is important to be cognizant that the physical environment itself, including the built, unbuilt, the way it’s laid out, the master plan setting and every element therein including the humans and their social structures, all comprise and function as security elements. Security as a theme and design priority finds its way into every aspect of design in the physical world.

For example consider a ‘door’, the simplest element of the physical world and one of the oldest and traditional security devices.

The assembly of these in Figure 2, shows a series of doors, varying mainly in their security function and related expectations. In other words, they vary in the levels of ‘security by design’ based on the design and material of construction.

The skill and technology of achieving security by the judicious use of design are termed ‘security by design’, … This science and art are being used extensively to secure people and their belongings from phones to nuclear installations. The emphasis here is to mitigate threats and vulnerabilities through the use of design which may include physical, technological, social and psychological factors.

Crime Prevention by Design

Within the security mindset, prevention is always the preferred approach and CPTED (Crime Prevention through Environmental Design) is one such strategy heavily patronised and researched internationally. For us in India, many of its principles resonate with our home-grown practices and social norms. The second generation CPTED principles have been operating culturally since centuries, even though they may not have been as systemised theoretically. However, it is the first generation CPTED that establishes the clear correlation between the design of an environment (its design, ambience and occupancy) and its impact on the opportunity for a crime.

The Association for Building Security India (ABSI- (www.buildingsecurityindia.com), the Indian chapter of the International CPTED Association (ICA- www.cpted.net), has undertaken many researches into the workings of CPTED in the Indian context. One such field experiment into the ‘Bazaars’ of Delhi has showcased that the community organisations within these markets, high levels of commissioned and casual surveillance, crowd control and secondary activities keep the CPTED principles thriving, securing them at negligible costs. A valuable finding was that CPTED principles remain deep-seeded in traditional design approaches that favour sightlines, encourage community participation, territoriality and maintenance. Read the complete case study on Lajpat Nagar Market of Delhi and many others from India in the book titled

A generation of urban development has given us the hindsight to know and relate the exact workings of the CPTED principles. We should now be applying these to our buildings in a renaissance of the traditional wisdom. There are many macro and micro aspects of the design of urban environments that merit security examination for their direct or indirect impact on security and vice versa.

A classic example to showcase this is the ‘gated community’. Conventionally this term denotes a real-estate model of residential developments, the main marketing appeal of which is based on being exclusive and secure. This calls for heavy expenditures and outlays towards hardening and organised security but the actual design of these communities contradicts most CPTED sentiments. While the objective is appreciable, the methodology of isolation creates these safe silos, unconcerned with the rest of the city.

The contribution to the city here is not nil but in the negative. The high security havens standing on the principles of exclusion and disconnect, install dead perimeters, killing all interactions with the city, offering no eyes, activity or community participation. The residents ‘feel secure’ within but are even more vulnerable outside the perimeter. This primary strategy of termination of all interaction with the urban context, takes away a vital function of civilised society. While they do nothing to improve the security outside the gates and walls, they also take away the opportunity to contribute to the city’s security and add to the opportunity for crime.

This privacy vs security function has been a topic of much debate for decades. Creating havens that are secure and hence more livable is justifiable but not in their current avatars. They are only addressing the symptom, not the disease. Security can only be comprehensive, not piecemeal. Only when the city is secure, can every element therein be really secure. In the meanwhile, the gates are only pushing the issues to outside the boundary walls and adding to them in multiple ways rather than mitigating them.

At first, these seemed like the obvious security solutions but criminological research over the last 50 years have brought forth the short-sightedness of these practices and their long-term socio-economic impacts that create larger security challenges in pushing them to the fringes. Contemporary climates of socio-economic sustainability and inclusivity, necessitate more wholesome alternatives, not alien to our traditional cities.

All high and opaque compound walls separate individuals from the community and endanger both sides. While on one side of these walls, the streets are rendered lonely, without eyes breeding crime, they are not helping the occupants of buildings on the other side either. The same dead compound wall on the inside, also affords a potential offender the unhindered opportunity to commit his crimes, screened from surveillance or community action of any kind.

Most of our Indian cities have witnessed that as the threat of crime rates escalates, the first action in defence is to raise the perimeters and disconnect. As the practice of higher, non-interactive boundary walls proliferates, the community action dwindles and the crime rates spiral. The simple solution, to restrict the height and opacity of these to achieve their purpose without sacrificing connectivity, is already documented in the building codes. Now it’s time to enforce and correct the course for the future, to undo the decades of damage and recapture how we live.

Counter Terror by Design

Indian cities and public spaces face the combined onslaught of high crime rates and terror, while dealing with huge human populations. Research shows that extreme man-made events typically use the high-value environments to multiply the destruction and thereby the ‘terror’. They manipulate the structural components into weapons of mass destruction, in a manner that the very building designed to shelter its occupants, turns against them and causes the maximum hurt and loss of lives.

Like all other crimes, the best strategy is to prevent these from happening. To achieve that, a little more is expected from the built environment, beyond the CPTED action. In such circumstances, security by design is even more effective in making the physical measures achieve this goal.

From the overall master plan to zoning the major assets therein, wrapping each asset in the necessary layers of physical control, including the strategic circulation patterns, selection of materials, interior finishes, services’ routes, structural design and operational security, everything performs best when they are in sync with the architecture. Subtle micro-detailing in the design can make the commonly installed devices more effective and ergonomic.

For instance, say we need a perimeter treatment for a high risk building as the first line of defence, to be designed to offer crash resistance. There can be many design solutions to enable the same without opting for the usual dead opaque boundary wall that kills surveillance and interaction with the city. The fixation with boundary walls is an Indian phenomenon in stark contrast to global high security benchmarks, achieved with less obstructive and more efficient means. The figure 5 shows a crash barrier located at the entrance of the Emirates Stadium in London to protect the public plaza from drive-by attacks. The creative solution shown here effectively serves it purpose while enhancing the security and without a shred of militarization.

Similarly there are many known techniques to manage vehicular access control where the design itself limits the speed of a vehicle at approach, its angle of impact and the worst-case scenario for rogue and malicious intent. Security provisions including the checkpoints, guard rooms and CCTV control rooms perform best when devices supplement the physical design in ergonomic patterns and not vice-versa.

Baggage scanners and human checkpoints are the most common points of interaction between security and the common man. While the end-users can benefit from a bit of design to soften the experience, the security regime would benefit immensely from a carefully evaluated location, conscious of the structural and ventilation impacts. Ample space provisions for appropriate circulation of those checking and those being checked are essential to avoid contamination and allow proper functioning and maintenance of the machines for effective performance. These should be complemented with interior design to aestheticize the experience.

Aesthetics is not a primary skill of security professionals. They are many times not even aware that there are aesthetic ways to install the same security which can reduce the harshness, enhance dignity and mollify the attack on sensibilities during a security check. This is however the stronghold of the design fraternity and it needs to be demanded of them. This is an urgent requirement in India as we are fast getting used to the threatening public environments and they are increasingly becoming a part of the Indian culture.

Often the architects, planners and interior designers are equally unaware of their role. Typically they just allocate the space demanded of them without diving deep into the mechanics and operational logic of the space designed, because it is a subject they are not traditionally trained for. They feel unqualified to venture into the subject pertaining to life safety or even discussing it. But when it comes to imagining and carving the most efficient circulations and simulating scenarios, they are the experts. While the security professional’s job is a difficult one, bearing the responsibility of hundreds of lives in a given built environment, the designers also share a part of it.

Security by design is the teamwork of the security and design professionals. Research shows that more often than one can imagine, an ill-informed design not only misses an opportunity to mitigate risks but actually adds to the vulnerabilities. The onus is on all professionals engaged in the design of built habitats to ensure that as a minimum expectation, the built structure must never contribute to destruction in any way.

This is the second line of defence offered by the science of security by design, in the form of resilience in the event that prevention fails, like a ‘plan B’ for the high-risk public environments in India, frequently under terror alert. It is critical to understand that all project types do not necessarily attract the same security consideration. There is no one-size-fits-all solution but a scientific approach that needs to be adopted. The level of ‘designed-in’ security expected in the PM’s residence is not expected in yours. Similarly, the level of security embedded in the design of a Parliament House has to be different from that in a Mall or a school.

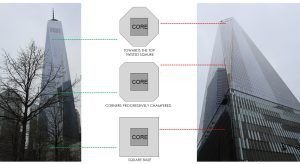

The One WTC building in New York, a modern day Icon of ‘integrated security’, offers a lot of lessons on the merits of the ‘security by design’ approach. Its history makes it more than ‘just an office building’ with the highest ever structural threats and design expectations. Despite this, the design process for the new tower commenced in the conventional way and it was only when the NYPD exercised its powers that the architecture was reinforced to respond to the very factors that had felled it originally.

But it was late in the design process, just on the brink of construction. There was not much that could be done then, to rectify the master plan for the 9/11 Memorial complex, that positioned this globally targeted tower, not more than 20 metres from a busy route, without much to shield it from fatalistic intent. The only recourse available then, was a structural redesign, reinforcing the base with blast proof walls, made of 3 feet thick RCC, up to a height of 200 feet (approximately 20 floors).

While this intervention renders this tower untouchable by anything that happens in its immediate vicinity, it comes at a heavy cost. Besides the additional construction cost, estimate the cost of the lost real estate for the most premium 20 floors of this iconic tower, because it is not possible to have habitable floors within the heavy structural walls that do not permit windows. And yet, whilst the tower is the most resilient in the world to the known structural threats today, it remains vulnerable.

What could have effortlessly and inexpensively been addressed just by a more judicious location in the master-planning of the Memorial complex, created such a drain on the resources and continues to do so even today as the NYPD has to maintain vehicular restrictions to overcome such vulnerabilities. Let’s note here that both are alternate ‘security by design’ solutions. The opportunity to locate the tower strategically was a cost effective and preventive option that was missed and hence replaced by a costlier, more cumbersome but more resilient and permanent one.

Also consider that the façade and overall form of the towers were already approved when the NYPD stipulated bullet-proof and blast resistant glass. Simply speaking, it’s just a change of specifications but the consolidated impact of all such design enhancements, at a late stage in the life of the project, to compensate for the absence of consideration to security at the design stage, resulted in the final cost of construction escalating to more than 3 times.

Compare this to our own Akshardham Temple in Delhi, constructed at a fraction of the cost while mitigating comparable risk levels. This is owing to its traditional design approach that inherently embeds security in the design philosophies using introverted layering strategies, grounded form, material selection and strict enforcement of non-negotiable security policies, pertaining to personal belongings, phones etc.

A quantification of the level of effective and integrated securities in the designs of these two monuments, generates almost the same scores. While this is surprising when we compare the audacious posture of the One WTC vs the humble unassuming stance of the Akshardham Delhi, it is testimony to the broad spectrum of possibilities offered by the ‘security by design’ approach, from the simplest, most cost-effective and tried-tested to the most complex, technical and technological, as the case may be.

Significantly, we surmise that security by design does not cost more and if embedded at the early stages of a project can actually reduce the security expenditures by 15 to 20%. Add to this, the fact that the security thus achieved is expected to be more efficient and effective.

In that respect, it is heartening to note that all investments into the infallibility of the One WTC, turned out to be sound business decisions. The iconic tower offers the most expensive real-estate in the world, fetching its promoters almost double the commercial revenue compared to the rest of downtown Manhattan. This is the premium paid for the enviable tag of ‘the most secure destination in the world’ and a true reflection of the pride of place that ‘security’ enjoys in human existence. This is also an indication of the demand for real, effective, perceptible and certifiable security that is integrated and embedded in design.

The author, Dr. Manjari Khanna Kapoor, a practising architect, academician and security Integrationist, is the pioneer of ‘security through architectural design’ in India, propagating the concepts of CPTED and counter terrorism through design. She is the: Vice- President at the International CPTED Association (ICA), Founder President of Association for Building Security- India (ABSI), Author and Chairperson of the SEQURE standards and audit methodologies and of the book ‘Security by Design: protecting public places against crime and terror’, published by Taylor and Francis of U.K.